4-1: Dockerfiles

In the last chapter, we used a Dockerfile to build an image for Impacket tools. That was cool, but wouldn't it be even cooler if we could write our own Dockerfiles to make our images?

That's what we're doing now.

Read the Docs!

I'm going to tell you up front that we will not be covering every single instruction you can use in a Dockerfile. I strongly recommend you review the Dockerfile reference and keep it handy as you go through this chapter—and anytime you're creating a Dockerfile, really.

What Is a Dockerfile?

From one point of view, a Dockerfile is a program. It's a set of instructions to Docker that tells it how to build an image. Simple enough, right?

Let's complicate it.

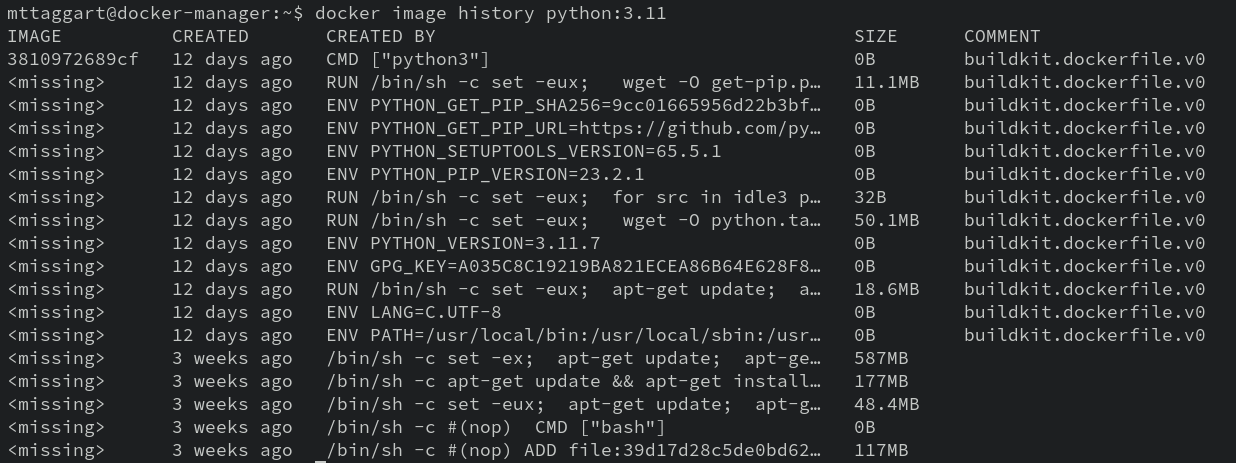

From another point of view, a Dockerfile is a list of changes, which become layers atop the base image. A really cool way to see this is docker image history. Check out the history for one of our Python images.

What you're seeing, in reverse chronological order, is every instruction that went into the Dockerfile to make the image. That's why the "first" one is the CMD instruction, which determines the default command to execute when the image is run as a container.

Writing the Dockerfile

But we're getting ahead of ourselves. We're going to make a new image from a Dockerfile, so let's get get up. Start by making a new folder called mynodeapp, and moving into it.

mkdir mynodeapp

cd mynodeapp

As the name might suggest, we're going to be making a tiny NodeJS application. But don't worry, you don't need to know any JavaScript to make this happen. That part we'll handle for you. Download mynodeapp.zip and extract its contents to your mynodeapp folder. You should now have a src folder that contains all the application code you'll need. No fuss, no muss.

Using any text editor you like, create a new file called, originally, Dockerfile. It's actually a "magic name" that Docker expects for certain operations.

FROM

The first line of our Dockerfile is the FROM command. This defines the base image on which we'll build. So yeah, it's not entirely from scratch, but base images are reasonable starting points.

The Node Image Page shows a ton of tags to choose from. I like to use the latest version with an Alpine flavor. As of this writing, that means the 20-alpine tag. So our instruction is:

FROM node:20-alpine

Don't worry that we haven't pulled the image yet; Docker knows what it needs to do during build. We'll get there.

COPY

At this point, we have a base image with NodeJS installed, but it doesn't yet have our source code. We need a way of loading it into the container.

"Don't you mean 'load it into the image?'"

Yes, but no. Remember that the build process creates a series of containers, the last of which is saved as an image.

The COPY instruction works exactly as you think: COPY <src> <dest>. We can use relative paths, and we can create new directories with dest. Let's make a directory called '/app' in the container, which will represent what's in the src.

COPY ./src /app

WORKDIR

With our code copied over to the container, it would be nice if we could cd to the new directory, so subsequent commands don't all need /app. We can do just that with WORKDIR. All future instructions will execute from that context.

WORKDIR /app

RUN

Node apps usually have dependencies as defined in package.json. Ours has one dependency, but it's critical. We can install it using npm, the Node Package Manager. It's available in the container; we just need to invoke it. The RUN instruction runs shell commands in the build container. We'll run npm i, short for npm install.

RUN npm i

ENV

Our Node application operates as an ad-hoc web server, which means it needs receive requests on a TCP port. We've seen how to forward ports to containers with docker container run -p. But which port to forward? A glance at our source code would inform image builders that the default listening port is 8000, but the code also watches for the NODE_ENV environment variable and uses that value instead if set.

We can use the ENV instruction to set default environment variable values. Do not use this for secrets! It's common for secrets to end up as environment variables when working with containers, but this is not the way to get them there. We'll discuss secrets management in a later chapter.

ENV uses a key=value syntax.

ENV NODE_PORT=8000

If you really want to test this, make it a different number than the default. Remember that later when we run the container!

EXPOSE

We've established our app's source code can tell us what ports are being used, but we shouldn't require builders to review source for that information. That's what EXPOSE is for. it doesn't actually forward any ports—rather, it's a kind of annotation embedded in the image's history that can inform container users what ports they'll need to forward.

EXPOSE 8000

ENTRYPOINT

Last instruction! We want our app to launch automatically when the container runs. That's what ENTRYPOINT is for. It tells Docker how to start the container.

Now there is also the CMD instruction, which would appear to do the same thing. What's the difference? ENTRYPOINT gives us a little more flexibility, because we can use it in conjunction with CMD to provide additional arguments. Also, interestingly, when a user explicitly adds a command to docker container run, it is overriding anything in CMD, but not ENTRYPOINT. That means we can have a base ENTRYPOINT and add more arguments at runtime.

TL;DR, use ENTRYPOINT if you intend for the same command to run every time the container launches.

ENTRYPOINT node ./

Remember we set

WORKDIRto/app, so the./in that command refers to the current directory. Node then searches forindex.jsin that location and executes it.

Full Dockerfile

So, all together, we've written:

FROM node:20-alpine

COPY ./src /app

WORKDIR /app

RUN npm i

ENV NODE_PORT=8000

EXPOSE 8000

ENTRYPOINT node ./

This is our complete Dockerfile! Of course, this is by no means the entirety of what we can do with Dockerfile instructions. For example, ADD has some powers COPY does not, such as fetching material from remote Git repos.

I'll again encourage you to refer to the Dockerfile reference.

Building the image

Time to build! We've already seen how docker image build works. Let's use the image name mynodeapp.

docker image build -t mynodeapp .

Our image should now be available and visible in docker image ls.

Running the Container

At long last, we can run our app container! Please run it detached, or your shell may be forfeit!

docker container run --rm -ditp 8000:8000 mynodeapp:latest

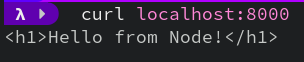

If all has gone according to plan, we should be able to curl localhost:8000 from our host and receive data from our app!

We can also run docker container logs against the running container to see the Listening on $PORT message, confirming the app works.

Modifying NODE_PORT

Before we end, I want to touch on modifying environment variables. Although we defined NODE_PORT in the Dockerfile, environment variables can be overridden with the -e option flag. So if we run:

docker container run --rm -e NODE_PORT=8001 -ditp 8001:8001 mynodeapp:latest

We will now be able to curl localhost:8001, and docker container logs for our new container will show Listening on 8001. The app still works, but on a port of our choosing!

Congratulations on creating your first Docker image! Now that we know how to make them, we need to learn how to publish them. That's up next.

Check For Understanding

What is the difference between

CMDandENTRYPOINT? When would you use each?Create a new image from

ubuntuoralpinebase images that runs a custom script when the container launches.